Ancient Fertilizers (Part 1): A history of fertilizer usage and evolution through time

Agriculture was a development in human history that revolutionized the way humans lived and formed communities in ancient civilizations. The ability to grow enough food to provide for a family or village inspired the permeance of modern culture. Although agriculture is one of our oldest technologies, it has been slow to innovate, often with hundreds of years between meaningful changes in land management. Even today, many of the practices that we use have origins that are thousands of years old. Fertilizers are a great example of a practice that has followed agriculture through time, starting from rudimentary beginnings and evolving into modern industrial processes.

Thanks to British researcher Amy Bogaard and their archeological surveys we can be fairly certain from N-15 deposits in ancient farmland that humans were applying manure at least 8,000 years ago! N-15 is a nitrogen isotope that is more common in manure and its levels can be measured in ancient grains to indicate if manure was used during the plant’s life. Due to the domestication of farm animals and dedicated farming, archeologists hypothesize that ancient farmers would have noticed the increased fertility in lands grazed by animals. As humans strayed away from the nomadic lifestyle and towards permanent fields and pastures, it was only a matter of time before they began manually applying manure to increase their yields. This practice was a predominantly European advancement until it spread to what is modern Palestine, Syria, and Jordan around 3000 years ago. The difference in usage is likely due to environmental conditions and customary practices of each culture. Early humans in Europe typically ran more intensive herds and grew different grains which may have contributed to this significantly earlier adoption of fertilizer. Dr. Some studies have even gone as far as to suggest some early agricultural societies in Europe would have raised beef primarily for the production of manure, like the Cucuteni, a culture that lasted from 5500 BC to 2750 BC in Southeast Europe. Only about 10% of the Cucuteni diet was beef, while Isotope levels of pastures signify intensive grazing. The other 90% of their diet was grains and cereals which may indicate that cattle and animals were kept in some part for their meat but primarily for the manure they produce. To further this theory there is evidence of fields being treated with manure around this time. The isotope levels indicate this culture would have kept cattle away from crop fields, either with fences or other methods, intensively grazed the cattle, and then harvested the manure and applied it to fields.

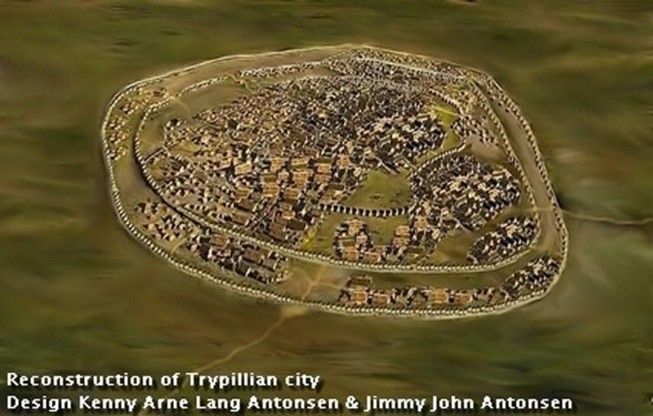

The largest of early Cucuteni city is thought to have housed up to 50,000 people, and needed hundreds of hectares of farm land to support its population. With the power of fertilizer, these extremely early cities could feed and maintain such a large population in concentrated centers.

Across the globe, in Asia, fertilizer was also being implemented in fields that produced cereals like millet, wheat, barley, peas, and lentils but ancient Asian cultures took a slightly different approach. It is theorized that farmers in China could have been using green manure as early as the 11th century BC, we know almost certainly that by the 7th century green manure was in common use. This is evident by some poetry included in “Shi-jing” the oldest collection of Chinese poems “if weeds remain undecomposed, millets do not grow thick”. Another manure thought to be used around that time would have been Tu-fen a mixture of animal and human feces with clay and plant ashes. These early farms often featured toilets next to the pig pens, it is thought these manures were typically combined and used together. This use of manure also became more common in Japan as the population grew and less land became available this practice also continued well into the modern era. Typically, farmers would plant until a field became exhausted then left that field fallow to recover - planting new land in the meantime. As land scarcity increased with population size, resting fields in fallow periods fell out of fashion. The use of human manure, or night soil, allowed farmers to maintain their soil by nutrients extracted through farming. Nightsoil became such an important product that every city and village in China was collecting it. In 1911 more than 182,000,000 tons of human manure was collected every year. Some cities such as Shanghai even develop canal networks specifically for transporting night soil, and private businesspeople were able to make careers transporting it from the cities to the farms. In 1908 a Chinese businessman paid $31,000USD for the right to remove nightsoil from a region of the city, that money today would be worth around $1,062,000USD.

Around the same time, fertilizer became more common in Asia, its use also became more common in South America. Mammals weren’t the only go-to poo for farmers though, in South America, birds were the star of the show, specifically the Guanay Cormorant.

This handsome bird not only helped fuel the largest civilization of ancient South America (Reaching a population of over 8 million) but also inspired some of the first-ever enforced conservation policies. Guano is an extremely effective organic fertilizer, typically containing 8-21% nitrogen, ~12.5% phosphate, and ~2.5% potassium. (Rodrigues, 2021) This free natural fertilizer piles up by the ton along the western coast of South America, sometimes reaching layers that are tens of meters thick. Although guano has coastal origin, it reached the Andes through llama caravans that trekked loads of nutrients into mountainous terrain. This fertilizer was so nutrient-rich that it was able to help sustain the Paracas Civilization that survived in the Andean desert for over 500 years.

Machu Picchu, the capital of the Incan empire, is over 850 km from the nearest coastline, this distance would be a difficult trek through any conditions, not to mention through the steep Andes. The effort of the llamas was well worth it, with this guano, the Incan empire thrived and was able to grow a variety of crops. In turn, the Incans protected these birds with the full force of their empire, killing one of these birds or disturbing one of their nests was punishable by death. The Incans even understood the breeding habits of the birds, and boats were not allowed to land on the guano islands during the mating season.

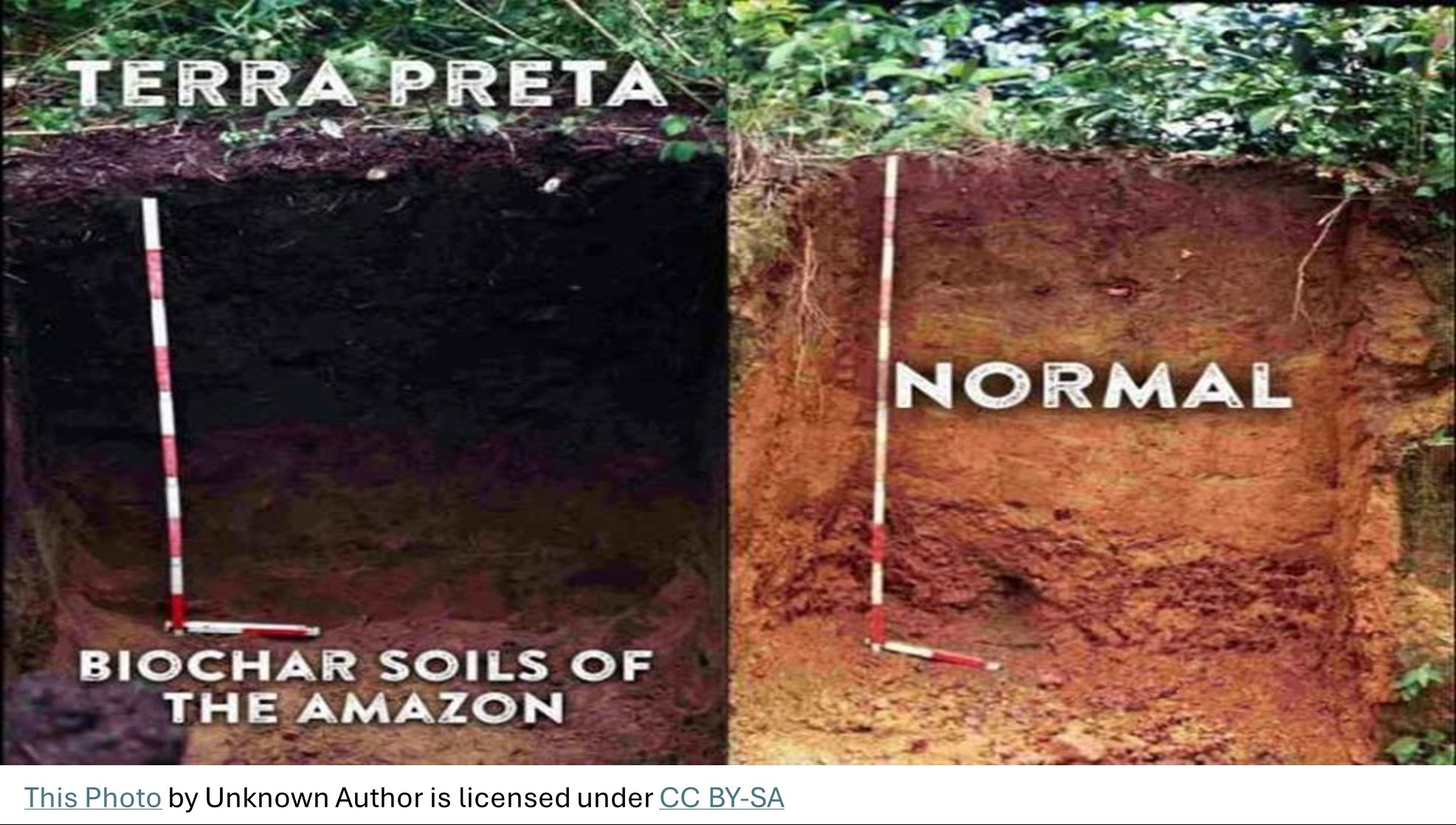

Further inland, Amazonian tribes developed their own methods to enhance soil fertility. They created patches of rich, high-carbon soil known as “dark earth” by composting food waste and layering it with charcoal and ash from controlled burns. This practice allowed them to grow more intensive crops in the otherwise acidic Amazonian soil. These dark earth sites, still visible today, represent an early form of potash, extracted through wood or plant ash. This simple potash was used in various ways across the world, from ancient Egypt and China to medieval Europe and early American settlements. Potash, produced from wood ash primarily supplies potassium carbonate which is highly beneficial to soil and plant health.

The evolution of fertilizer has been a cornerstone in the development of agriculture, shaping the way we cultivate and sustain our crops. From ancient practices to modern innovations, the journey of fertilizer is a testament to human ingenuity and our relentless pursuit of growth and sustainability.

But our story doesn’t end here. In the next part of this series, we’ll explore fertilizer use on a recent scale, covering major advancements and different methods of fertilizer creation over the last 500 years.

start your soil journey today

contact us